From John Hennessy:

Seventy years ago this month, Fredericksburg, like the rest of America, was mobilizing for war. There was little in Fredericksburg’s experience to distinguish it from thousands of other towns across America, but still the rather frantic arousal that followed Pearl Harbor offers up some interesting tidbits about how World War II would reverberate across the American landscape.

On the evening of December 12, 1941, the military call—666—sounded on the city’s fire alarm system, summoning the Virginia Protective Force. The Fredericksburg battalion of the VPF, commanded by former WWI pilot Captain Josiah P. Rowe, had been mustered in March 1941. It numbered sixty men, and since March had been drilling weekly for precisely a moment like this–when they would “provide a force of trained men to render protective service in an emergency during absence of the National Guard on active duty.” That December evening they hurried from across the city, assembled, and received orders to protect Fredericksburg’s strategically important landmarks: the Embrey Dam above Falmouth, the Chatham Bridge, and, most importantly, the Route 1 bridge over the Rappahannock at Falmouth.

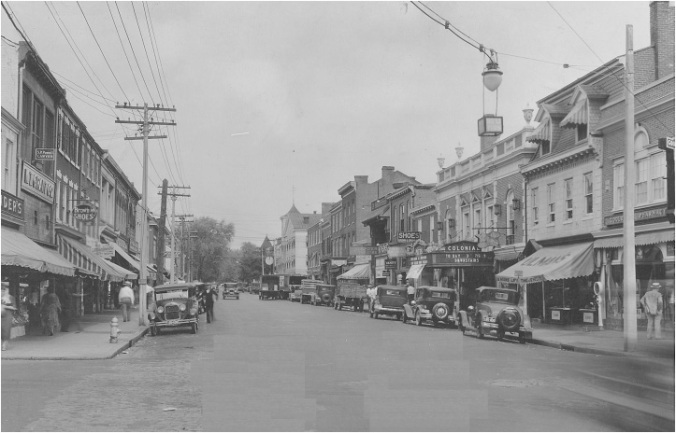

The most important strategic asset in Fredericksburg--the Route 1 Bridge at Falmouth, under guard by the Virginia Protective Force in December 1941 or early 1942. Central Rappahannock Heritage Center.

Of those landmarks, the only one that would receive extended attention was the Falmouth Bridge, which would be guarded 24/7 for many weeks. The VPF strung lights beneath the bridge to illuminate the work of any would-be saboteurs. One man constantly patrolled the span, while two kept watch from below. For a time, the soldiers stopped and inspected every car that crossed the bridge (traffic would be backed up for 20 miles if that happened today), but even in 1941 and 1942 that proved impractical. Continue reading